|

A GUIDE TO AUTOGRAPH AUTHENTICATION

We could easily present a few hundred thousand words about the current autograph market and still be miles from the finish. There are volumes to write on all aspects of autograph collecting, from rarity to values to preservation to current trends. This article looks primarily at the retail market for private collectors, those purchasing signatures of notable figures such as Thomas Edison, Helen Keller, Mickey Mantle, Babe Ruth or perhaps presidents and famous generals. Today, hundreds of thousands of people collect such autographs, perhaps even more. Autographs have been an important collectible for centuries. In the 1800s, American and European collectors systematically acquired documents and clipped the signatures to mount in albums. Imagine the disservice done to history, not to mention the collectibles market. Napoleon, Washington and Shakespeare signatures, neatly clipped, and the entire remaining document tossed in the fire. At least today even the most unsophisticated or money-driven dealers and collectors know better.

If you are a novice to mid-level collector of autographs or signatures (which are, of course, obtainable for virtually every category of "celebrity" imaginable, from athletes and actors to politicians and painters), most buyers want some level of certainty that what they're buying is genuine. Museums typically purchase items of historical or other significance, rather than just someone's signature, and they have more resources for authentication. But in many cases, authenticity is critical to value. So, how can you "guarantee" authenticity? The first rule of thumb: Buy from someone you trust. Beyond that, the world of authentication is an exercise in self-education.

What about the heralded letter or certificate of authenticity available from most every dealer? It should be no surprise that dealers in autographs specifically, or historical or sports items in general, nearly always offer a scrap of paper authenticating each item. As the saying goes, it usually isn't worth the paper it's written on.

Over the last decade or so, the sports collecting world turned away in part from mass-produced, and therefore devalued, cardboard baseball cards to focus more on autographs and game-used memorabilia. And as they did, forgers began cranking out bad signatures almost as fast as card companies produced "rarities" still valued at a few bucks in catalogs but worthless in the marketplace. Seemingly overnight, estimates grew until experts (the real ones, not the phonies!) believed that anywhere from 50 to 90 percent of all autographs on the market were fakes!

These numbers are so astounding that it's almost impossible for collectors to comprehend: Picture a nice three-ring binder of your favorite baseball cards. Then put a big black X on somewhere between 4 and 8 of the cards in those 9-card sheets. Whether you're collecting 2001 football cards or 1961 baseball cards, and whether they're worth $20 or $20,000, just picture what that notebook would look like, your collection devalued by half, or virtually all, due to forgeries.

True, there are trimmed and altered cards to make a $60 piece of cardboard look like a $600 one; but that's a minor problem compared to the fake signatures that faced the market for several years.

For our clients, and many collectors, there was a silver lining of sorts in the realization that the market had plummeted more than last year's real estate values. (And for anyone outside the collectibles industry, don't pooh-pooh sports and related memorabilia and collectibles. We're talking about a multi-billion dollar annual retail market.)

That astounding number of forgeries for "all" autographs was dramatically skewed, because 99 percent of the signatures in the marketplace were from contemporary baseball, basketball, football and hockey players. These players were signing autographs by the thousands for a clamoring audience of adults more than kids, and it's quite likely that one might have seen, say, 25,000 new Major League baseball autographs hit the marketplace in any given month. Of that total, perhaps only 100 were vintage baseball (1880–1960), entertainment or historical signatures. This, of course, is a very broad but educated estimate, because no audited tallies exist, but even if our gross estimates miss the mark by 50 percent it illustrates the point dramatically.

The illegitimate autographs were generated from many different directions. Some stars refused to take the time to sign, so it was more and more common to have team balls penned by a team employee for the big-name athletes. It was a form of legitimized forgery for decades in baseball, but that was a practice when dollars weren't involved. Rather, it was to salve the unending desire for fans to have their heroes' signatures—in 1910, 1930, 1950 and up into the modern era. In the "old" days the system for autographing baseballs was straightforward. Team management placed baskets of balls by team lockers and asked players to sign them as time permitted after games or practice. Players would grab 15–20 balls from basket A, sign them and deposit them in basket B. As the process was repeated, it was easy to capture the team on balls. Occasionally we find a vintage ball with two signatures of the same player; a player might have forgotten he signed on Monday and then went through the basket routine a few days later. Or, some players on the roster at the time might be missing on the vintage ball—because they were too busy, were injured that week or simply forgot.

Occasionally the big-name player let his ego intervene and what is known as a "clubhouse" or "secretarial" signature was added. Experts today always examine the stars' signatures more carefully if the players were known to have passed off the task to a team employee. As we will discuss further, this occasional problem of the 1960s has only been exacerbated by arrogance among players in the current era. We heard from one NBA publicity director who was irritated at having his staff always asked to sign team balls with a reticent star's name!

With the 1980s and 1990s bringing huge paydays for players who signed, fans were suddenly asked to pay $5, $15, $35, $50, $75 and more to obtain the autographs once considered a treasure gained for hard work, perseverance and no cash! As one would guess, when big bucks entered the picture, so did forgers. Dozens—hundreds?—of modern athletes can't verify their own signature scrawled on a program, picture or ball they signed the day or week before by the dozens at a fence for free, or by the hundreds at a table for a fee. Thus counterfeiters began selling signed photos by the tens of thousands—all leading to the fact that most kids and adult collectors probably have as many bad signatures as good ones from athletes of the very recent past. In this case, the "recent" and "problem" areas we're focusing on are mostly the 1990s, but with various problems persisting into this new millennium, too.

Fortunately—or more accurately, unfortunately—forgery remains more of an art rather than modern graffiti when the target is Babe Ruth or Ty Cobb, Abraham Lincoln or Thomas Jefferson.

Collecting the prized autographs of athletes, entertainers or politicians used to be a wonderful hobby. It was as popular in the 1860s as it was in the 1960s. Many of us, as kids at the time or adults trying to relive our childhood, could connect with our favorite players—or our dad's or grandfather's—via autographed balls, cards, 3x5 cards, photos and more.

Collecting rare historical signatures has always been for the more sophisticated and affluent, but new generations changed the definition of affluence. In 1963 we wouldn't have considered paying for a Mickey Mantle autograph, nor would our fathers. Our generations stood at fences, bullpens, clubhouse doors and parking lots hoping for the treasured moment when The Mick or another hero would step into our field of vision and take that pen to sign for us. We would wait at the park for hours for that opportunity.

Just thirty or so years ago, when I was looking for artwork to illustrate a baseball history article, "cost" wasn't the issue in finding a card or signature of Hall of Famers Hank Greenberg and Sandy Koufax; just finding a local dealer was the bigger issue. I actually had to go out of Seattle to get the cards I needed on short order. There was no crowded internet with dealers then! But shortly thereafter the world of sports memorabilia and autograph collecting exploded. Suddenly stars who played for less than $100,000 annually could earn that much or more in a year on the signing circuit at card shows.

Smiling 10-year-olds were shoved aside by greedy adults anxious to buy the autographs for resale, or to forge them for the same purpose. The hobby became a business, and a very lucrative one for both the honest and dishonest sellers.

For those of us at the center of the historical and collectible maelstrom, perhaps the most astounding aspect of the craze-industry to sell signatures is the number of people who knew—and still know—literally nothing about what or whom they collect—or sell. Listening to a self-proclaimed knowledgeable dealer rattle off mispronunciations, statistics and information on athletes, movie stars, politicians and someone's hero is painful, if not pitiful.

We see 30-year-old buyers and sellers who more or less know the names of Negro League players, for instance, but are clueless about which ones might never have been able to write—or sign their names; they routinely mispronounce the names of players about whom they know nothing; and overnight they become traders and self-styled experts in signatures of all-star hockey goalies, big league pitchers and Supreme Court justices. Way too many wouldn't know the difference between a General Robert E. Lee and a Colonel Sanders signature, but they'll buy them and sell them, and be happy to authenticate them for you, as well.

|

Far too many autograph dealers today couldn't distinguish a General Robert E. Lee autograph from a Colonel Sanders.

|

I should interject that I'm not negative about every aspect of this business; quite to the contrary, I love it. I love every bit of the writing, research, buying and selling I do in these very diverse fields, but I hate to have to be so vigilant because of the number of fakes and other problems with which we all must deal.

Take a moment to review the scenarios below, all quite real, and how the good, the bad and even the ugly find their way into not just private, but even museum and library collections.

Expert A: This expert, like most other retail autograph and sports memorabilia dealers, will give you a guarantee or certificate of authenticity (COA) of some sort on virtually any autograph he sells. For each signed ball or document he'll include an 8.5x11 or card-sized COA, most likely stating that "I, Sam Smith, guarantee the authenticity of the autograph for as long as the buyer owns it."

So the embossed COA is pretty, and it's reassuring, but what does it guarantee? Note that when the item leaves the buyer's hands it is no longer guaranteed. While that limitation might make sense so that it no longer could be returned to the seller for a refund (since a secondary owner didn't purchase it) why would it not be guaranteed in perpetuity by the authenticator?

Who is Sam Smith? Why, he's your neighbor's uncle's boss and he quit his job at the car dealership or Home Depot or the coin store to "follow his dream" and open a retail baseball card/entertainment memorabilia store.... He may be honest, but his expertise might come from having collected whatever it is he's selling for "more than five years"—or perhaps five minutes. He may even be pretty darned good about telling the difference between a genuine and a phony Mickey Mantle autograph. But he probably doesn't know the difference between, say, Jackie Robinson and Frank Robinson, and he's arguably a little lean on experience when it comes to, say, Civil War generals.

Mr. Smith, if he's honest, can provide you a moderate sense of comfort if you're within his own comfort level. If he's not so honest, forget it. He may be one of the many sellers who don't know the difference between a Mickey Mantle and a Mae West signature, and certainly not an early 1950s Mantle and one signed later.

Remember, too, that many of the sellers are just like the buyers-anxious to believe and consequently, often liable to purchase and sell seemingly (to them) good signatures that are fakes.

We once visited a major antique store in Chicago where we had acquired quality, genuine World's Columbian Expo items in the past. The owner had a beautiful 1930s vintage baseball photo on his wall, signed "Babe Ruth"; many customers inquired about it, but he wanted it to adorn the wall and refused all offers to buy. To those experienced in historical baseball signatures—experts and average collectors alike—it was a blatant, almost humorous, example of a forgery.

The dealer proudly said he bought the signed photo from an old-timer who had it personally signed by Ruth. Even elementary study of Ruth's signatures through the years would have shown that it bore no resemblance to the real thing.

Expert B: Once you get past Expert A, the inexperienced retailer who may unknowingly help fill the market with fraudulent material (and who causes just about as much damage as the guy who knowingly sells phonies) you're in a new world of authentication. When purchasing historical or other autographs, it's one thing to recognize an obvious fake; it's often even more difficult to be absolutely certain something is real. Our Expert B, Joe Jones, is one of the 10 percent or so of the sellers who know enough to be called an expert on some level and who may even be accepted by insurance companies to perform appraisals.

In the historical and entertainment fields Mr. Jones has studied signatures for years and learned a lot; it helps him in his business and it means he may be as knowledgeable as almost any one of his customers when it comes to certain areas of his personal expertise, such as American presidents, astronauts, World War II generals and so on.

As a collector and buyer, you have learned as you go and you have known Mr. Jones for years. Perhaps you've purchased most of your collection from him. You and he have two things in common: Interest in the same areas of collecting and knowledge gained by paying attention and repetition. You may have seen 100 signatures of Generals Patton or Eisenhower and you know them well. Your expertise in, say, Winston Churchill, is limited to the signature you saw in a book. When it comes to Civil War General Robert E. Lee, you've seen dozens for sale and dozens more in print, but you've never personally examined one. Your dealer-expert Mr. Jones has, however. In fact, he's bought and sold two and they looked fine to him. They might well have been the genuine article. But did your expert know enough to study the ink, the paper, and the document on which it was signed and other key factors?

Just like everyone's, Lee's signature changed a bit over the years. So did Mantle's and so did Lincoln's. Dealers weak on expertise might reject a genuine early signature or accept one that had the wrong slant of the letters for the decade signed.

You're comfortable and so are Mr. Jones' other customers. His reputation grows with the years. He's made a few key mistakes, but they've never been discovered and may not be until your son sells your collection thirty years from now and it becomes painfully apparent that your George Washington and Jim Thorpe are fakes. Intent was never an issue!

Expert C: Many buyers think that if an expert is independent (not a seller), he must know his stuff! In reality, Arnie Anderson, our "independent" expert, could well be someone who also sells (or buys), but happens not to be doing so in this particular instance; he could also be the blatantly dishonest "expert" who buys under one name, sells under another and authenticates under still another! The fact is that the most knowledgeable experts in narrow fields are usually a) those who collect the specialty and b) those who sell the specialty.

In autograph circles, like coins and stamps, there are independent firms that both grade and authenticate. PSA, for example, began as one of the two major authenticators for baseball cards and unopened packs (another staggeringly expensive field in some instances), then began doing the same for signed memorabilia and non-sports items, including historical signatures.

When these folks say a signature is "good" they're probably correct most of the time. When they say something is "bad" they often are overzealous or mistaken or may lack expertise in that specific area and are "uncomfortable" going out on the proverbial limb to say "it's good" even if they think (but don't know) that it is. Too often, these authenticators are not paid to take the time necessary to do their job properly. You can't research and authenticate an obscure individual from the Depression Era in 20 minutes; you can't study a Lincoln autograph properly in two hours! We have seen far too many cases where the authenticator returns the item as rejected, but without an opinion that it is "good" or "bad." They may label an item "suspicious." This often is a cop-out and casts a negative pall on the item, the owner and the last seller. In reality they didn't have the time or expertise to justify their concern nor any sound reason to consider it suspicious, let alone fake. On occasion they will say "we cannot tell" and then reject it, primarily trying to be cautious and not wanting to be on the hook for an authentication error.

|

Too often, authenticators are not paid to take the time necessary to do their job properly.

|

Clearly, in most cases, Expert C has more expertise and also a reference library that make his job easier and him more reliable than Expert B much of the time—but not all of the time by any means.

Expert C can cast doubt, question, even reject, but his main goal is to ensure he does not authenticate a fake. The result is that we see far too many "we can't verify" evaluations.

Naturally, no owner of a signature wants his or her piece labeled suspicious; most collectors and buyers run away from a possible purchase when they hear a third-party authenticator has refused to authenticate—just as fast as when the authenticator has called it "bad." That is grossly unfair to the item and its owner. Sports hobby authenticators/ "slabbers" will tell you that a "can't verify" is not intended to be a negative label; but that is how it appears in the marketplace if it is revealed.

The Best Expert? Expert A hardly warrants the appellation. But whether you select Expert B or C, they should use more than just a guidebook to evaluate signatures. Loops, descenders, crossed t's and myriad other details are invaluable as initial guides to making a decision. So are the context and history of the signature, which are often sorely ignored. If context were a required criterion of analysis, far fewer autographs would be authenticated.

We talked to an autograph collector incensed at a baseball "expert" who, at a memorabilia show, deemed his prize a fake. The signature was too sloppy, the capital letters were wrong, and so on. It didn't match the Baseball Hall of Famer's signature that the expert had seen dozens of times. Then the collector pointed out that he had obtained the autograph the previous day—at the same show where he'd sat in front of his hero, chatted with him and watched him sign (scribble) the item.

How could it be? The authenticator was using all the proper benchmarks for the autograph of the star from the 1940s through the 1970s; but here they were in the 1990s and the signer was older, but still strong and impressive for a man his age. The previous "exemplars" or examples/samples and key aspects used "by the book" were outdated. One of the important points to remember is that as signers age, they don't just become shaky; they often change minor or even dramatic techniques in their signatures. Breaks between letters that were never there before become routine. The well-known flourish at the end of the last name may now be a simple line. These are not "old age" signature problems; they're changes in one's signature later in life. Many celebrities, politicians and athletes change their signature early in life, also. In their early twenties, they may have a more formal, stilted or even childish signature; once they began signing thousands of times, their style changes, often incorporating more new characteristics and/or becoming more uniform and consistent. And, as most movie stars and sports figures will tell you, their signatures penned at 25 per minute at a performance are virtually unrecognizable to anyone, including themselves.

Abraham Lincoln's classic signature was simpler in his early days as a congressman. Mickey Mantle's trademark loops beneath each "M" were absent as a younger player. You need to know and understand the period in which someone signs. There are also keys to forgeries: Professional forgers want to match characteristics that are well-known. They want to forge single-signed items that are the most valuable, not items with multiple signatures about which they know nothing.

Checks are favored as the "canvas" for autographs by many collectors because they're virtually never found in the marketplace forged. It would pretty much require someone to find a blank book of checks, or to "wash" existing checks to change a signature (from the lesser known or not-so-famous spouse/celebrity). But if that's ever happened it's been a rarity. Many sophisticated collectors eschew common signatures and single signatures, preferring the obscure document or group signature that forgers ignore. But there are some forging techniques for every eventuality, such as taking a page of ten or so New York Yankees' signatures and adding the big star that might be missing—Ruth, Gehrig, DiMaggio—conveniently at the top or bottom. One caveat is always to avoid such sheets (common in earlier years) if the big name could've been added on later. But if you want assurance on a more common autograph, what can you do?

|

Conduct your own research independent of an authenticator or seller; take the time to learn about the signer, the specific autograph and the context in which it was written.

|

Too often you may receive only a simple authentication with your autograph; as we've noted here, you should be able to evaluate the evaluator. If you're independently paying an authenticator, don't be afraid to ask for facts and supplementary information, not just "it's good" or "it's bad."

Historical context is a great measuring device, and for the astute collector, an enhancer of the value and collectibility of the autograph. Can you identify the context? Can you date the signature? If it is a document—as opposed to a check, for example—can you personally conduct your own research parallel to the authenticator's so that you know the likelihood that it is genuine? A side benefit here is that your research will most likely provide you a good benchmark with which to evaluate your authenticator.

Many signatures are obtained on photographs. Can you ascertain the vintage of the photo as well as the vintage of the signature? You don't want to purchase a magnificent signature of a celebrity or athlete signed in Sharpie or other felt-tip pen on a 1940s document—years before felt-tip pens were available—unless it makes sense that the signer added his autograph years later.

Your authenticator should know inks, pens, documents, papers and other related components that help date and thus authenticate signatures. An expert will recognize the difference between 19th and 20th century papers, as well as ink characteristics. Baseball Hall of Famer Ty Cobb was well-known for his green ink letters and signatures, but we have seen botched forgeries using a color that not only isn't correct, but wasn't even available in his lifetime.

Remember that you are buying opinions as well as facts. Today, as we were finishing this article, we were presented with a George Washington handwriting example. Could we authenticate it? Frankly, not easily, and even though it was priced at fraction of the usual price for a Washington signature we would question its "value."

It was one word—a single word!—clipped from an allegedly authentic document written by Washington. Obviously the seller, or a previous seller, acquired a Washington document, perhaps for $5,000 or less because it had faults or stains or other problems. In a stroke of genius, he came up with a wonderful (please recognize our sarcasm here) marketing opportunity. He could sell single words in Washington's hand for hundreds of dollars each and turn a bad $5,000 document into a profitable purchase.

Whether the single word is forged or in Washington's hand, we would have to say it's virtually worthless in our eyes. There's no purpose, context, importance—value! Who wants the word "horse" or even "British" allegedly in Washington's hand? A sentence or two is tough enough, but it may be enough (unsigned) to establish the historic soundness. Think about a clip from a document from Washington that said, "Martha took sick this week and I worry desperately that she may not see the Spring. What good would I be as president as such a heartbroken man?" Well, authenticate that partial letter and it would be the rare exception and quite valuable. But if it just said the weather was bad, the horses were old or worse, just the single words "horses" or "weather," just what value could one apply to them because they were in Washington's hand? It is not uncommon to see a portion of a document or an unsigned note for sale. It is easy to see potential value or historical interest in whatever that excerpt or piece may be, but a single word clipped from a document is ludicrous in virtually all cases. What next, a $50 special—a capital "W" in George's own hand?

Remember that so often the person who spots the bad autograph—or the good piece that everyone has overlooked—is not the dealer; nor is it Smith, Jones or Anderson. It's the smart, hard-working collector. It's you.

|

|

|

|

2010 #1, January–February

A Guide to Autograph Authentication

Baseball Card Autographs: Facsimile, Fake or the Real Thing?

What Happens When Two Nearly Identical Rarities Are Offered Simultaneously?

A Review of HK222 Proofs from the WCE

Another 'Expert' on eBay

What About That So-Called Quarter...or Dime?

World's Columbian Ticket Prices Realized

World's Fairs and International Expositions Since 1851—A Handy Guide

Announcing The History Bank's First 2010 Auction—World's Fairs, Olympic Games, Disneyana

Baseball Card Autographs: Facsimile, Fake or the Real Thing?

One of the most popular ways to collect baseball autographs is on baseball cards.

How many fakes do you think have been sold, allegedly signed in Sharpies years before Sharpies were even invented? Early cards were signed infrequently, so if it's from before the 1950s question the signature no matter how good it looks.

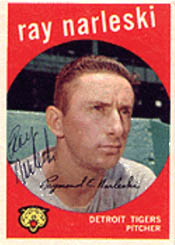

Shown here are three 1959 cards signed by the appropriate players, very possibly at the time of issue in the case of Narleski and Averill (in ballpoint); Marshall's, in felt pen of some type, was probably signed after his playing days at a card show. Just because Narleski or Averill used a ballpoint doesn't mean they signed the cards in '59. They might have signed them in 1960 or years later. It has been common over the last 25 years to have ball players, including "journeymen" rather than stars, sign on their vintage cards.

|

|

Finally, remember that Topps' player facsimile autographs on cards are just that—facsimiles with no intent of looking real. Interestingly, Topps put facsimile signatures on cards for years, but don't try to "authenticate" using those signatures. They often do not match the real thing. Note here that Marshall's and Averill's hand-signed signatures match the facsimile signatures fairly closely, but Narleski's ballpoint signature bears no resemblance to the printed signature on the card.

At shows today, most old-timers—players in their 70s, 80s or even older—are happy to sign, and the signatures generally are outstanding unless age has intervened; get a bunch of 1990s and current players together and they'll often scribble away in the scrawl they've become accustomed to on the autograph circuit.

SPALDING SPORTING GOODS MORE FAMILIAR THAN ITS FOUNDER

|

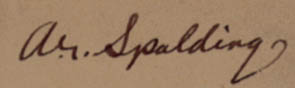

In the history of baseball, few had an impact greater than Albert Spalding. Yet today, he's hardly recognized as a name alongside Ruth, Mantle, Rodriquez, Clemens, Bonds and many other vintage and contemporary signers. And since he died nearly a century ago, Spalding's autograph is seldom traded; consequently, studying it can be difficult. But shown here is a quality, legible example. He virtually always signed as A. G., not Albert, and the "G" is often unidentifiable to the novice collector. A Hall of Famer for his pitching (his won-lost record was an amazing 253–65), Spalding is best known for the sporting goods company he founded in 1876, as well as the early promotion of that novel invention, the baseball glove. As with all uncommon and expensive autographs, the signatures should be scrutinized carefully. We always prefer a signature in context, meaning clips (from a larger document) are less desirable. But often, a clip is the only option available to you. A document signed by Spalding is very rare and quite easily could cost $5,000–$10,000 depending on the nature of the signed document; you could hunt for such a piece for many years. A cut, on the other hand, might be much less difficult to find and commensurately less expensive, say "only" $1,500 or so, but with it comes the greater likelihood of forgery. One more caveat: Don't get stuck with a very expensive autograph of musician Albert Spalding by mistake! A. G.'s nephew (1888–1953) was one of the 20th century's premier violinists.

The most popular 19th century autograph? It's the 16th President, hands down!

Amateurs, or even moderately experienced collectors and dealers, might balk at the Lincoln signature shown here. It doesn't match the generally expected (or accepted!) more upright "A" and "L" of the last name. But this signature is from the 1850s when Lincoln was a congressman, not his later and more well-known presidential signature. This Lincoln signature is clearly in fountain pen and old, and on an equally old and absorbent paper. There should be no doubt about the age from that standpoint. In fact, the signature is on the cover of a paperbound Congressional Directory that belonged to Lincoln, its provenance from the estate of Lincoln's Secretary of the Navy, Gideon Welles. A voracious collector of Lincoln artifacts, Welles left a significant estate of autographed items and other Lincolniana, some of which still remains in the family.

|

|